Editing And Tuning

If recording a song is like framing a house, editing and tuning is like sanding before painting.

Editing and tuning used to be very different techniques than they are today. In the days of %100 analog recording, the editor had to be much more committed and hands-on. The editor would literally take a razor blade to tape and shorten or lengthen the offending bar or beat to correct timing errors in a drum recording. And correcting a tuning error usually meant re-tracking the part entirely. Then computers become the heart of the studio...

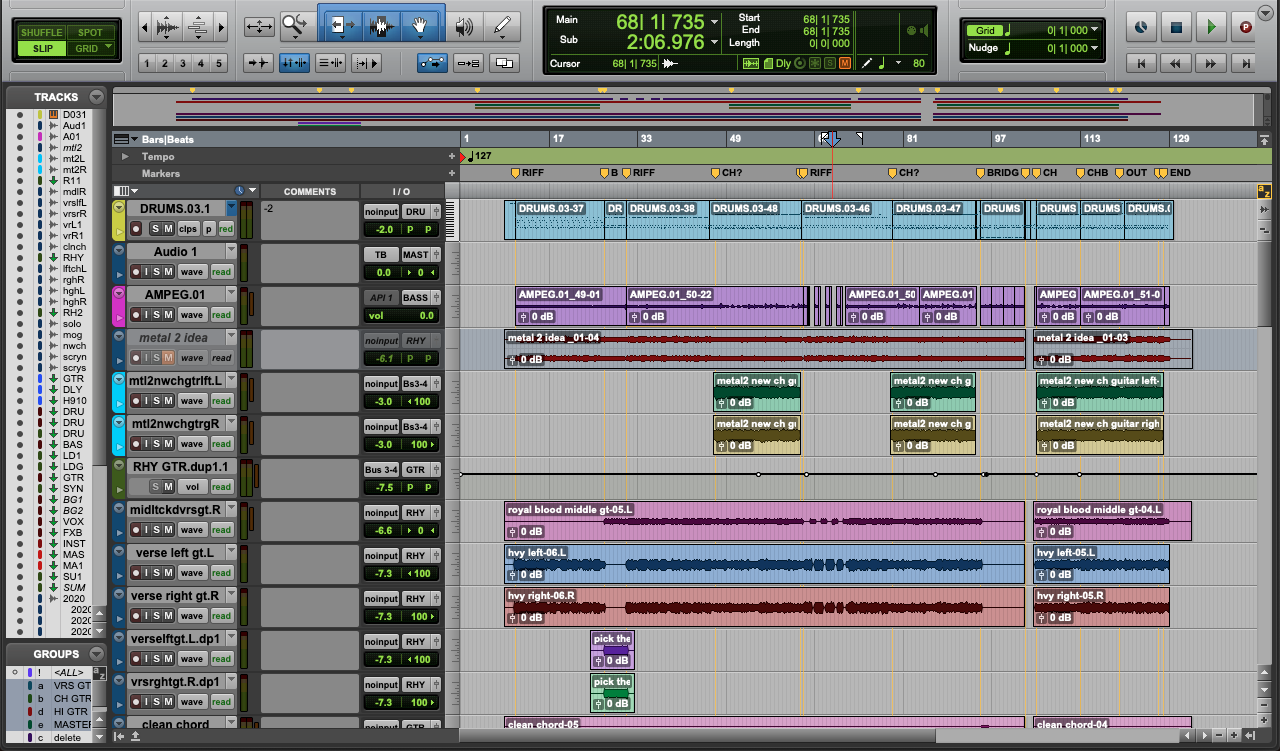

If you’ve used a DAW (Digital Audio Workstation) before, you’re probably familiar with their editing powers. A few ‘click-and-drag’ motions and you can do anything from slide a snare sample a few milliseconds in time, or you can reorder the entire structure of a song (that’s actually one of my favorite uses during songwriting: “would this bridge sound better before or after this part?” Click, drag, listen.). The real power in editing, much like in recording with live mics, lies in the details.

There are obvious uses of editing, such as eliminating unwanted noise in-between lead guitar notes, controlling the sound of a singer’s breaths between lines, and tightening up the timing of a sloppy drummer. But the lesser thought of uses are just as powerful, and result in a more impactful sound without drastically altering the band’s performances. These are a few of the many things we look at when working on your recordings.

The Phase Edit

When you have two microphones recording one sound source, the audio energy from the source (speaker, drum head/shell, vocal chords, etc) hits the microphones at slightly different moments in time. When you combine those slight out of time sounds in the mix, they can sound thinner, tinny, muffled, or flat. This is because they are out of phase (the more correct verbiage for "“out of time”). To correct this, you can use the edit window of your DAW. Zoom in to a peak in the waveform of one of the two mics as far as you can. See how one hits the very top slightly before/after the other? Click and drag one of the two microphone files, slide its peak slightly closer to other’s peak, and listen. You ear will tell you when it’s right, and that take will sound better. And your mix engineer will love you.

Downbeat Edits

Phase edits also apply to whole band moments. Think the downbeat of a chorus. The kick, bass, guitar/keys/kazoo, etc are hitting at the exact same moment. If you zoom in on the waveforms, however, you’ll see minute timing differences in their downbeat peaks. Carefully aligning JUST the first note on all instruments will make your choruses hit much harder at the start, without altering the performance nuances that follow.

I could write a book on phase alone, and you’ll see a lot more about it in coming articles. But now, on to…

Groove Edits

Groove edits and timing edits are almost one and the same. The difference lies in how you look at the grid behind the audio files. The grid shows exactly where subdivisions exist throughout your piece of music (assuming you recorded your music with a metronome). But you may have noticed, the groove of the song may not land on directly on a divisions of the beat. That is the skill drummers work to develop: how to keep the feel of the song before, right on, or after the actual beat of the metronome. Some genres of music are built on a particular push or pull feeling against the actual tempo. Reggae likes to pull on a beat, landing behind the pulse of the song at times, giving you that relaxed feel, and bluegrass likes to push ahead at times, for example. Thus when you are editing an instrument in a song to match the groove, you want recognize what groove decisions the musicians made during tracking.

When doing timing edits, the grid tells us where the ‘one’ is, where the quarter notes are, where any note division we set it to show lies. That reference allows us to get a kick drum to hit EXACTLY on the one, for example. With a groove, however, we need the grid to see where the part doesn’t hit right on the grid. Once we see that relationship between grid and performance, we can edit the other parts in the song to match the groove of the song.

For example: the bass player nailed the take and really holds the song together rhythmically. The drummer didn’t quite lock in, however. If we look at the bass take against the grid and use it as a guide, we can then edit the drum performance to closer match that bass, further cementing that groove in place without losing the overall downbeat of the song.

Again, the grid only applies if you recorded the music to you DAW’s metronome, but the groove editing technique can be use regardless, and the band will think they sound more like themselves.

Backing Vocal Edits

Backing vocals are an interesting part to edit. You can apply the same editing philosophy that you use for lead vocals, but since backing vocals are often a unison musical part with multiple vocal tracks, there are some tricks you can use to make life easier.

The end of a line is the first place I usually look for inconsistencies. Chances are, the last note of each of your background vocal tracks end at slightly different moments in time. Maybe that works stylistically for your song. If you want it tighter, however, separate the sound of that note ending from the start of the sound. Drag the end into alignment with the lead or the other background vocals, and crossfade the note and the ending. Repeat with all backing vocal tracks and you’ll start to hear that polished pop vocal sound. The effect becomes more pronounced the more backing vocals you have in the song. And the vocalist may feel like their performances sound much more intentional.

Tuning

Tuning, much like editing, can be used as a ‘fix-it’ measure to salvage an otherwise perfect take, or it can be used as its own form of creation (think T-Pain and modern pop/hip-hop productions). Personally, I am a fan of Celemony’s Melodyne software, and have used it on every record I’ve worked on in some way. Again, there are the obvious uses (fixing a flat or sharp note, pitching up a drum to match the key of the song better), but the less obvious uses are worth mentioning…

The Fake Background Vocalist

Many times, when working with a band on a strict budget tracking a whole record in a weekend, we run out of time for backing vocals. Or maybe I’m working with a new band who’ve never written backing vocal parts before. In either case, you can take the lead singers performance, duplicate it to another track, and pitch that performance, note by note, up or down to your heart’s content. This allows you to either create a faux backing vocal for the final part or to simply start writing the backing vocal parts prior to tracking. This method does introduce a unique timbre to the backing vocals, depending on which software you use and how you use it. You might find it pleasing or displeasing for the finished part, but it won’t distract from its use in songwriting.

The Voice of God (Or Angels)

This one is simple: similar to our tuning tricks above, if you duplicate a vocal, guitar, or drum part to another track and pitch it up or down a full octave, you can create a whole new impact, from deep, earthy, or even ‘devilish’ sounds, to angelic, whiny, or ‘chipmunk’ sounds. Sky’s the limit, but sometimes adding a little bit of either octave in can up the overall impact of the part.

As you can see, there are probably an number of ways to use editing and tuning to improve the quality of your track, or to create something entirely new. We keep an open mind and find the best way to improve every song we get to work on. How do you use editing and tuning on your music? Tell us in the comments, and ask any questions this article may have raised!